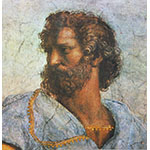

Son of the physician to the king of Macedonia, Aristotle joined Plato's Academy in Athens in 367 B.C.E., where he stayed until his master's death in 347. After tutoring the future Macedonian king Alexander the Great, he settled in Athens, where he founded a famous institution called the "Lyceum" or "Peripatetic school" in 335.

Aristotle authored fundamental works in various fields of knowledge: The Organon (logical writings), Metaphysica, Physica, On the Soul, The Nicomachean Ethics, Economics, Politics, Poetics, and Rhetoric. Indeed, Aristotelian thought is intrinsically encyclopedic. It conducts an organic and coherent investigation of nearly every area of knowledge, proceeding from a few basic philosophical principles such as: the four causes, the dialectic between potentiality and action, and the distinction between matter and form.

Aristotle's "physics" relies on a qualitative analysis of natural phenomena, usually without recourse to mathematical methods. In Aristotelian cosmology, the Earth - a place of corruption - was located at the center of the universe. It was composed of the four elements: earth, water, air, and fire, which moved naturally in straight lines, either upward or downward. By contrast, the motions of the celestial bodies - the Sun, the planets, and the stars - were uniform and circular. To explain the independent motion of the planets, Aristotle postulated their rotation on concentric spheres. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, a number of authors - most notably Saint Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225-1274) - purged Aristotelian physics of the ideas that were incompatible with the Christian faith, such as the eternity of the world and the materiality of the soul. Aristotelianism became the basis of university courses, remaining broadly unchallenged until it came up against the claims of the new mathematical and experimental science.

One of the key tenets of Aristotelian physics is the denial of the reality of the void. According to Aristotle, an empty space is nothing but a contradiction in terms, space (or rather "place" - the Greek topos) being nothing other than the limit of bodies. Consequently, space (place) cannot exist without the presence of bodies. In the Fourth Book of the Physics, in particular, Aristotle goes on to show the paradoxes that, on the basis of this definition, would result from the acceptance of the real existence of a void.