There are many kinds of microscopes, designed for different purposes. However, there are only two basic models: the compound microscope and the simple microscope.

The compound microscope is an optical system composed of two stages (objective and eyepiece) for observing specimens at high resolution and magnification. The lenses are inserted in a rigid tube called the body-tube. A turning-point in the construction of compound microscopes occurred in the 18th C., when three different types were developed: a tripod version, a drum version, and a pillar version. For the first type, the decisive contribution was that of Edmund Culpeper (1660-1738). The second was the work of Benjamin Martin (1705-82), who designed a pocket drum microscope made of pasteboard telescopic tubes; at the base of the outer tube was inserted a mirror to reflect the light on the slides. The third type was produced by John Cuff (1708-72). To these were added other systems such as the binocular microscope, the Amici-type reflecting microscope, and the Pacini-type compound microscope.

The prototype of many British and continental microscopes consists of the compound microscope illustrated by Robert Hooke (1635-1702) in Micrographia (London, 1665). This model, which enjoyed considerable success, embodied innovations with respect to continental European microscopes, both in its optical system and in its sophisticated illumination apparatus.

The most common compound microscope of the 18th C. First sold by the Englishman Edmund Culpeper (1660-1738), who modernized the Italian tripod microscope by adding a substage reflecting mirror. The body-tube, made of wood, glued pasteboard, and leather, is inserted in a cylindrical support covered in rayfish skin. The cylinder is held by three supports fastened to a circular wooden base. Later models featured a box foot with a drawer for accessories.

Developed by the English microscope-maker John Cuff (1708-72), who used the suggestions of Henry Baker (1698-1774) to improve the microscope designed by Culpeper (1660-1738). Cuff introduced more sophisticated 18th-C. focusing mechanisms, and fitted the new model with a very long eyepiece. Cuff's innovation was the compound side-pillar, which allowed easy access to the specimen stage and the option of installing a fine-focus mechanism. The Cuff-type microscope is generally mounted on a wooden base, on which a square-sectioned pillar supports the body-tube.

Compound microscope fitted with two optical tubes allowing observation with both eyes. Some special versions, called stereoscopic microscopes, give a better, three-dimensional view of objects.

This type of reflecting compound microscope, used in the early decades of the 19th C., was invented by Giovanni Battista Amici (1786-1863). It eliminates the effects of chromatic aberration by means of a mirror placed opposite an opening in the body-tube. The mirror reflects the light to another concave mirror placed at the end of the tube, which in turn sends it to the eyepiece. This microscope was very popular for a time, but some of its drawbacks (including the fact that the magnification could be varied only by changing the eyepiece) eventually caused the system to be abandoned. Chromatic aberration was later eliminated by an effective combination of different lens types.

This type of compound microscope, invented for biological observations in 1844 by the Pistoia physician Filippo Pacini (1812-83), is mainly characterized by its stability and its sophisticated, efficient focusing system. The filters are inserted into a disk on the stage. Was particularly appreciated by some outstanding microscopists.

Special type of compound microscope, developed c. 1850, in which the specimen is illuminated from above and observed from below. A prism placed under the specimen reflects the light rays into body-tube. This feature made it possible to observe chemical reactions without visual disturbance from the gases or the effervescence generated by them. For this reason, such devices are also known as chemical microscopes.

Compound microscope in which the specimen can be cross-lit by a beam of polarized light generated by a suitable prism (such as a Nicol prism). A similar prism inserted in the eyepiece serves as an analyzer. Microscopes of this type are often used in crystallography and mineralogy to study crystal structures thanks to the special images and color patterns that they generate when they are traversed by polarized light.

The lucernal microscope uses an oil lamp as a light source. Perfected by George Adams Junior (1750-95). Adams's models were imitated by other makers such as Robert Banks (late 18th C. - first half 19th C.).

This microscope, also called projection microscope, illuminates the specimen by means of sunrays and can be used to project the specimen image on a screen or wall.

Microscope for high-precision linear measurements. Used, for example, in many optical instruments to read finely divided scales.

The simple microscope is a converging optical system—often a simple lens—that makes it possible to reduce the observation distance and thus to increase the apparent size of the object. For small magnifications (typically up to 3) it is customary to use a simple lens ("magnifying glass"). Greater magnifications are obtained with a "Stanhope lens," a "Coddington lens," a "Wollaston doublet," a "Steinheil triplet," etc. To preserve acceptable image quality, these systems usually go no further than 20 magnifications. A unique, limit case is the simple microscope invented by the great Dutch naturalist Antoni van Leewenhoek (1632-1723). It consisted of a tiny simple lens, with which the illustrious scientist was able to obtain extraordinarily high magnifications.

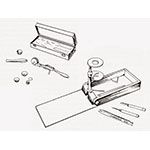

A characteristic of all these systems is that the image appears upright as seen with the naked eye, i.e., not upside down. This makes it easy to coordinate movements when handling the specimen observed, for example with dissecting microscopes. Moreover, the low magnification allows a wide enough working distance (distance between the lens and the specimen) to insert handling accessories. In sum, by comparison with compound models, the simple microscope produced less chromatic aberration and a sharper image. These characteristics were already recognized by Robert Hooke (1635-1702). Such optical performances made it more reliable than the compound microscope. But some features—such as the need to observe the specimens at a close distance, and the lack of illumination for observing opaque specimens—limited its use because of the eyestrain for the microscopist. Ideal for observing transparent and minute materials, the simple microscope found widespread uses in the observation of insects, plants, and small aquatic organisms placed in suitable holders or recipients, as well as in dissecting work. Often housed in a case fitted with many accessories (tweezers, needles, razors, and so on), the simple microscope reached its peak dissemination in the 18th and early 19th Cs. It later survived chiefly as a dissecting microscope. Even the simple microscope, like the compound one, comes in different versions: compass, aquatic, and botanical.

Special type of simple microscope in which the screw placed on the arm holding the specimen is controlled by a spring. Was very popular with naturalists because it proved to be an ideal instrument for observing insects and other opaque objects.

Microscope whose body-tube is held horizontally by an articulated arm. Was very popular among naturalists for observing organisms in an aquarium to which the device was brought up close.

A version of the simple microscope, very easy to handle. So called because it was used to observe plants.

Simple or compound microscope referred to as a "portable" microscope in the 18th C. A small, convenient model suitable for field research.