The following are some of the scientific academies mentioned in the descriptions of instruments at the Museo Galileo of Florence.

The Accademia dei Lincei was founded in 1603 by the young Prince Federico Cesi (1585-1630) who was joined by Anastasio De Filiis (1577-1608), Johannes Van Heeck (1574 - after 1616), and Francesco Stelluti (1577-1646). Setting as its goal the radical renewal of knowledge, the Academy launched a spirited attack against the dominant Aristotelian philosophy. It adopted the emblem of the lynx, symbol of sharp and penetrating vision. The Academy immediately grasped the revolutionary potential of Galileo's (1564-1642) astronomical discoveries and urged him to join, which he did on April 25, 1611. Its members supported his war against the bastions of traditional culture, and later against the hostility of ecclesiastical authorities. The Academy promoted and published Galileo's Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari e loro accidenti [History and demonstrations on the solar spots and their characteristics] in 1613 and the Saggiatore [The Assayer] in 1623. The Accademia broke up at Federico Cesi's death in 1630.

Founded in 1648 and recognized by the French monarchy in 1655. In 1663, at the behest of Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683), the Académie achieved its definitive status and its members were granted the privilege of calling themselves painter or sculptor to the king and queen. It was located first in the Louvre, then in the Palais Royal and, again, in the Louvre. In 1795, it became the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Founded in 1657 by Prince Leopold (1617-1675) and Grand-Duke Ferdinand II de' Medici (1610-1670), the Accademia set itself the task—in conformity with Galileo's teachings—of subjecting a series of natural phenomena to rigorous experimental proof. Such phenomena had traditionally been interpreted on the basis of the physical principles of Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.). The very name of the Accademia and its motto—provando e riprovando [testing and re-testing]—express its main goal: cimentare, i.e., subjecting the traditional explanations of natural phenomena to inquiry and verification. Noteworthy members of the Accademia included the secretary, Lorenzo Magalotti (1637-1712), Vincenzo Viviani (1622-1703), Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (1608-1679), Francesco Redi (1626-1698), and Carlo Renaldini (1615-1679). The Accademia concluded its program in 1667 with the publication of the Saggi di naturali esperienze (Examples of natural experiments) (Florence, 1667), which reported the main results obtained. Members focused their research efforts on thermometry, barometry, the physics of states of matter, vacuum physics, and the analysis of the aspects of Saturn.

Scientific society founded in London in 1660 by a group of naturalists who met near Gresham College. The initial impetus came from Robert Boyle (1627-1691), who sought to promote mathematical-experimental science in conformity with the teachings of Francis Bacon (1561-1626). The Society's initial period of activity ran from 1660 to July 15, 1662, when it was granted a charter by King Charles II (1630-1685). Subsequently, the Crown exercised the prerogative of appointing the President; however, it did not challenge the total independence of the Society, which received no funds from the monarchy. In 1665, the Royal Society began to publish the first European scientific journal, the Philosophical Transactions, which soon became a medium for disseminating the new scientific ideas. The Society's fellows included the leading scientists of England and Europe. Robert Hooke (1635-1702) was its long-serving Secretary, in charge of programming and organizing its experimentation sessions. For many years, the Society's President was Isaac Newton (1642-1727), who published his famous letter on light and colors in the Philosophical Transactions. The prestige of the Royal Society remained intact in later centuries. The institution is still active today and, at its London headquarters, holds one of the largest scientific archives in the world.

The French Académie Royale des Sciences was founded in 1666 during the reign of Louis XIV, on the initiative of his chief minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683), to promote theoretical research as well as the advancement of arts and trades. In contrast to the Royal Society of London, the Parisian Academy depended on the Crown for its finances and organization. The number of members was fixed. It established a hierarchical structure, divided by scientific discipline. In its early years, the Académie was remarkably active, securing the collaboration of France's leading scientists and eminent foreign savants. The Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), for example, was a key participant in the Academy's work for twenty years. The Academy declined after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), when many Huguenot scientists fled France. Completely restructured in 1699, it became one of the premier scientific institutions of the seventeenth century. It was finally abolished in 1792.

Cosmographic academy founded in Venice in around 1684 by Vincenzo Coronelli (1650-1718). Its members met at the convent of the Minorites, an order to which Coronelli himself belonged. The Accademia was headed by the Doge Marc'Antonio Giustiniano. The institution's status as the first geographic academy is recorded in the dedication of Coronelli's celestial globe preserved at the Museo Galileo of Florence (inv. 2366). Its activities are documented in several printed books containing lectures by its members. The Accademia was dissolved at its founder's death in 1718.

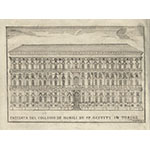

The Berlin Academy of Science was the brainchild of the great German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), who sought to create an academy on the French model—but free of State control and thus substantially independent. Leibniz saw such an institution as a vehicle for disseminating the German language, advancing science, expanding industry and trade, and propagating universal Christianity through science. This program served as a basis for the foundation, on July 11, 1700, of the Societas Regia Scientiarum, with the support of the Elector (later King) of Brandenburg-Prussia, Frederick I. The Academy won definitive recognition on January 19, 1711. Frederick II reorganized it and, at Voltaire's suggestion, appointed Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698-1759) as its director in 1746. The body changed its name to Königliche Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Royal Prussian Academy of Science). Through Maupertuis, the French language had a considerable influence on German culture. Suffice it to mention that French was the institution's official language. The Academy had its own anatomical theater, botanical garden, natural-history collections, and scientific instruments. Its most famous members include Jean Bernoulli (1667-1748), Leonhard Euler (1707-1783), and Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736-1813).

Founded in Florence in 1753, the Academy dedicated itself to the development and modernization of agriculture in Tuscany. Flourished under Grand Duke Peter Leopold (1747-92), who revitalized the institution. From 1767 on, the Academy was Italy's top advisory body on agricultural-economics issues and the main center for the study and dissemination of leading-edge technologies for the improvement of agriculture. In 1870, after Italian unification, the Academy became a State-run institution.

In 1757, Count Angelo Saluzzo di Monesiglio (1734-1818), the mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736-1813), and the physician Gianfrancesco Cigna (1734-1790) founded the Società Privata Torinese, which, in 1759, took the name of Società Reale (Royal Society). Its membership included such illustrious scientists as d'Alembert (1717-1783), Gaspard Monge (1746-1818), and Pierre-Simon de Laplace (1749-1827). On July 25, 1783, with the approval of King Vittorio Amedeo III, it became the Accademia Reale delle Scienze. In the nineteenth century, it was a highly active center for the promotion of scientific and technological research. In 1835, it started a major scientific prize, whose first recipient was Charles Darwin (1809-1882). The Accademia delle Scienze is still active in Turin.